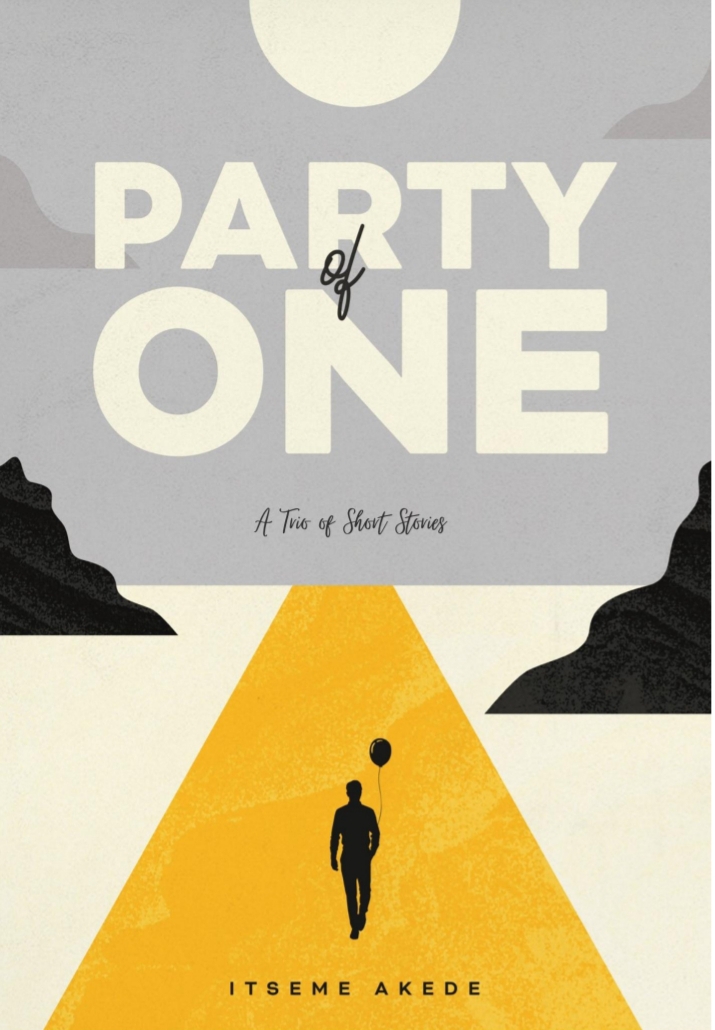

Title: Party One

Author: Itseme Akede

Year: 2021

Pagination: 56

Reviewer: Henry Akubuiro

Party of One is a collection of three short stories by one of Nigeria’s fast-rising literary stars, Itseme Akede. The author, a multi-genre writer, who often engages her readers with her short narratives and poems in her community newsletter, Letters from I, and on social media, sees creativity as a routine engagement with the reader, of which the scribbler is duty-bound to avail the readers of quality stories to feed their curiosities on a regular basis. The short stories in this collection enjoy a telling nous in rendering and a fabulous epistolary style. The brilliant mesh of styles sets the writer apart as one who does not wish to be stereotyped as a storyteller but a consummate writer who cooks a tale with all the flavours.

The 65-page collection consists of “They Have Come Again”, “Love Letters and a Half” and “Where Our Parts Meet”, partitioned as Book 1, Book 2 and Book 3. The issues treated in the tales range from postcolonial African condition, relationships and migration. Many African writers, including Akede, have deployed realism as a narrative vehicle. By doing so, they draw attention to the social malaise in society and how they have impacted life and the public space since post-independence.

Writing on “The African Realism and Influence in Literature” in the International Journal of Advance Creative Studies, Neelam Tandon states that African Realism “… emerged in the mid-20th century as a response to colonialism and the dominant European literary traditions that misrepresented or ignored African perspectives. African writers, such as Chinua Achebe, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, and Wole Soyinka, among others, were key figures in the development of African realism. Their works explored themes such as colonialism, identity, and the clash between traditional African values and modernity” (p.853).

In addition to depicting African realities, contemporary African literature, he rightly observes, has been influenced by a variety of cultural, social, and historical factors, including ongoing challenges faced by African nations in the post-colonial era. I add, too, that it’s not just the challenges faced by African nations today but the challenges faced by individuals and communities in Africa and diasporic experience. These conversations have enriched the African literary canon and the directions of postcolonial discourse.

Enter Itseme Akede with Party One. The first short story in the book, “They Have Come Again”, serves as a compass with which we see Akede’s social engagement. It x-rays man’s inhumanity to man, borne out of envy and hatred on ethno-religious basis. Above all, the author highlights terrorism in Nigeria, and how the innocent are made the sacrificial lambs for the interest of a few disgruntled elements fighting the system with violence. The story also teaches us that discretion is the better part of valour.

In the story, Adamma has given birth to her first male child ever, Obinna, or Obi for short. No matter how many girls a woman bears, the Igbo society where she married into will not accord her the same status accorded the mother of a son, which explains the joy that greets her delivery. The author brings African tradition into scrutiny in this fiction. Among the children of the family, dominated by girls, Obi is the only one allowed to go to school by his father. He, as time goes on, serves as a free teacher to his sisters at home, as he learns from the teachers in school. Thus, his neighbours begin to call him a teacher. One of her sisters, Nkiru, is later married off, hoping to learn more through evening classes with her husband’s permission. This is cruelty to the girl-child.

The story, in most parts, traces Obi’s life trajectory and his tragic end. He is to find a job as a teaching assistant at a university after graduating with flying colours. Obi, now nicknamed Prof when he enrolls in a PhD programme, falls in love with a girl named Ola, whom he met at a teachers’ training college, and both later get married. The topsy-turvy of life rears its ugly life as Obi loses his job, forcing him to relocate to the northern part of the country. But disaster strikes when his house goes up in flames, set ablaze by insurgents. “The insurgents had approached him a week before to join their movement, stand up to the government, pass their message across with bombs and violence, and he declined – violence had never been his choice weapon”, writes the author (p.17). Curiously, only his house is bombed.

Downcast, Obi is bemused as to why he relocated to this part of the country ravaged by terrorism. His wife is forced to flee the north, but Obi is adamant to follow her footsteps. The insurgents visit him again to convince him to do their bidding and kill his little daughter while playing to teach him a lesson. They follow it up with another visit to finish him off.

The same story features another narrator, Ola, who relates her personal experiences with Obi. She begins: “I was never in support of Prof wanting us to move to that part of the country. But what did my opinion mean? All men I had ever known only seemed to care about one thing, and that was their own agenda” (p 24). The narrator blames Obi for paying deaf ears to relocate to the north, knowing the political tension and insurgency there. She has lived to tell the story. Perhaps cowardice has saved that.

The second story, “Love Letters and a Half” is a hybrid of short tales about relationships, presented in an epistolary form. Letter One, entitled “Chide and Ranti”, is dedicated to Ranti, and it’s about an exchange between two lovers professing love. Letter Two continues the scribal love affair replete with endearing metaphors and hyperboles, while Love Letter Three offers an intoxicating love variety and fantasies. The writer of the third letter carols: “I liked to compare us to things; the last time, it was the moon and the stars. You were the moon, and I, the stars… you were specially sent for me” (p 44).

The third short story in Party of One is a heartrending story about black profiling abroad – the trials of African immigrants in the Western world. For want of a better life, these Africans or their parents flee their homeland, where, unfortunately, they are not accorded the same respect accorded whites on foreign soil. Often stereotyped, these blacks are suspected of every crime committed and roped in. The white interrogator, Agent Harris, in this story, wants Chike, a Nigerian immigrant in the States, who has lived there for seven years, to own up to raping a white girl and killing her, to which Chike responds, “I didn’t do it. My hands have never held blood in them.” Chike’s alibi is that he was not at work when the said murder took place. We learn from the narrative that, sometimes, innocent blacks have gone to jail for crimes they never committed.

From the media res beginning of the story, Akede takes us back to Chike’s homeland, Nigeria, to juxtapose his conservative foundation, finding the love of his life, Kami, and pursuing his American dream. But the dream ends in a shocking deportation to Nigeria for a phantom crime. Life, the story tells us, is not always a bed of roses for the African immigrant seeking greener pastures abroad. Akede’s short stories are written in an inviting, racy language.

Average Rating