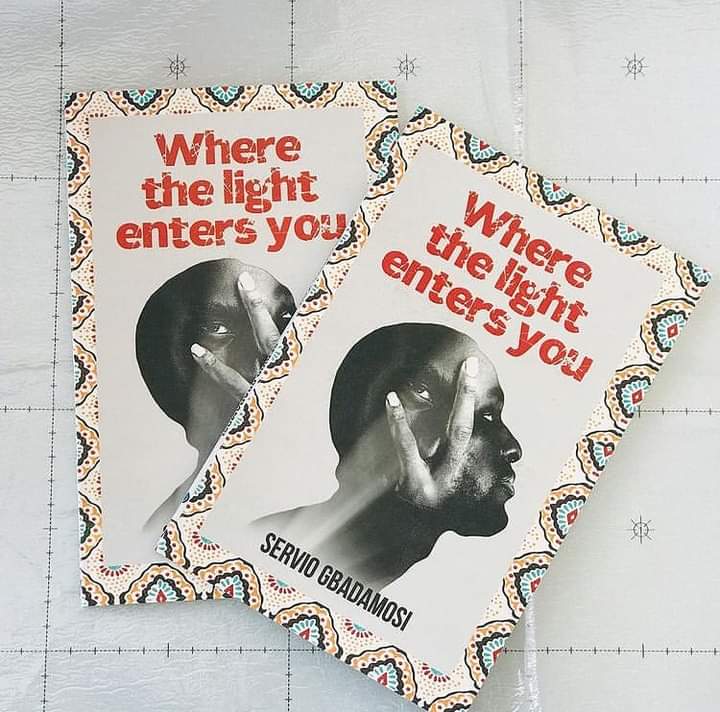

Book: Where the Light Enters You

Author: Servio Gbadamosi

Publisher: Noirledge

Pages: 110

In his deeply meditative and philosophical second collection, Servio Gbadamosi follows an interior narrative of human vulnerability. From an auspicious declaration of the poet’s return to poetry in the first poem “The Return”,—to examine no doubt all that he had been subjected to by the wiles of fate: “even when I knock at the doors of death/the soul of the earth becomes a rock”—the collection veers into its topic with élan. What is ever clear as one navigates the labyrinths of his poetry is how Gbadamosi brings us into an awareness of his metaphorical purpose: the idea that we, as humans, refract light and that light enters us at a spot where our constitution is most liable to be transparent; the idea, so to speak, is that our moral faults are also our liabilities.

Ecclesiastical imagery defines the lines of the poem, “Judas”, in which Gbadamosi examines the liability of guilt and betrayal. The poem ruminates on history and religion, and in the end, we are brought into an epiphany: “The heart is a sack of sin/its weight sinks the spirit.” What does the poet refigure as sin, in such an old-fashioned sense? “Sin”, in the poet’s reckoning, is “when a brother sinks a dagger in/your soul . . .”

Gbadamosi’s faceted vision pivots to the reinvigorating power of lacerating experiences. But, here, he twists it on its head: our ritualised attempts at living only serve to expose the natural betrayals we are surrounded by. Where “the living seem a little better than the dead,” the search for the true passion of living continues. The poet inevitably weaves Yoruba mythology into the loom of his poetry. This aspect of the collection seems to be an attempt to answer the atavistic origins of the heroic “other”—or those whose supposed betrayal went against the grain of the status quo. Enter Atunda, the renegade slave of Orisha-nla. Gbadamosi wants us to consider how the supposed betrayer or renegade could be the iconoclast, the unsung hero, whose very heroism is maligned by his nonconformity.

With this mythological background in “Atunda”, Gbadamosi considers love as a double-edged scythe of betrayal and becoming. In the annals of vulnerability, love makes the brave defenceless and helpless. But is that even bad? In one instance (in “First Love”), the poet tells us that it is. Love is to be considered deeply as the pulsating heart of something deeper, he says, but we find that, in life, the first stirrings of passion—because they are lacking in experience (he describes what he means exactly by experience in the poem “Living Memories”)—is always ephemeral.

One of the most wholesome poems in the collection, “With my daughter on a Sunday afternoon”, takes the vulnerability of love to the edges of sublimity. Here, our attentions are drawn to an image that irradiates innocence and love in the dreamy realm of the quotidian:

Trying to get some sleep on a Sunday afternoon is

an impossible task when you’re a father to a

boisterous little girl.

The poet lies on the sofa on a languorous Sunday afternoon in his sitting room while his daughter’s vivacity disturbs his attempts to sleep. But he finds joy in her presence—the light she brings or the fact of her being the very epitome of human love. Her personality pervades the room: “the living room bursts at the seams overcome by her playfulness.” In the poet’s configuration, light—in the sense in which it represents happiness—enters a person via the conduit of children.

In one instance, in “With my daughter… “, Gbadamosi shows us the vulnerability of adults in the presence of puerile innocence; in another instance, “A Well of Gladness”, love becomes the experience and intensity of genuine lovemaking (“the music of the sea their bodies play”) or the insidious reports of passion on social media and elsewhere in “For so long I have dreamt of love”.

One feature of meta-poetic collections such as this is the often thorough exploration of the consciousness of guilt as an examination of self in given cultural moments—aspects of which we find in Plath and Lowell as well as in Awoonor and Brew. Little wonder what Gbadamosi considers in “The Mesh” (his sequel to Brew’s poem of the same name). His “I am holding onto a crumbling pillar of faith” is a counterpoint to Brew’s “crossroads”—what the older poet called “the darkness of [his] doubts”.

In “Pour my guilt upon this land” the poet takes his conscience to the guillotine, his belief being that a country’s problem is the sum of the shortcomings of its people. Only when this collective guilt is acknowledged can redemption come. Do I agree with this? Not exactly. (Even the poet himself admits this ambiguity in “My sins are telling my mouth what to say”). The efficacy of such consciousness is dependent entirely on context. Where the context points distinct fingers at certain figures, then we can be sure of where the guilt of the land lies.

Gbadamosi shows influences across poetry, music and Yoruba mythology. Various poems dedicated to Okigbo, Awoonor, Osundare, and others, reveal a range of emotions which are especially canny in the way they capture the raw energy of poetic iconoclasm (as we see in “For Fela Anikulakpo Kuti), or the morbid but essential ruminations around mortality (as we see in “For Kofi Awoonor”), or elevated language of the Okigbo-esque poem, “Harmony of the Padre”, in which the poet explores, in epic proportions, conflations of violence and politics.

“Morunrayo’s Song” and “Home” show the other side of refraction. To Gbadamosi, home is where he yields to love, where he can let his guard down, and where he finds hope in abundance because he can be whatever he wants to be. In a collection that spans fifty-one poems, Gbadamosi brings an illumination before our eyes: while our most vulnerable moments could be moments of heart-sinking guilt, they could also be moments of love and happiness—moments when we are unguarded enough to imbibe the purity and taints of our humanity into our consciousness.

About the Author

Chimezie Chika is a culture journalist, essayist, and short story writer whose writing have appeared in The Question Marker, The Shallow Tales Review, The Republic, Isele Magazine, Iskanchi Mag, Lolwe, Efiko Magazine, Culture Custodian, Brittle Paper, Afrocritik, Afapinen and elsewhere.

Average Rating