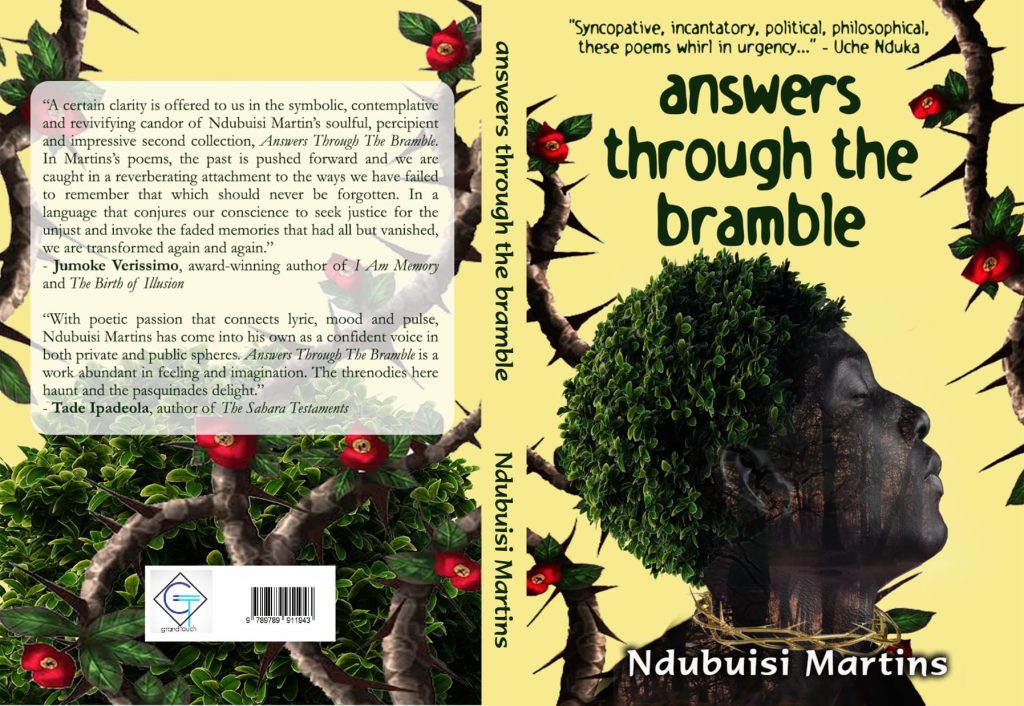

Ndubuisi Martins emerges into the literary firmament as an inquisitor who seeks answers, even if ruthlessly, in the most uncanny way. Here is a poet for whom questions are compasses for the navigation of sociopolitical and historical spaces. In his second collection, answers through the bramble (Grand Touch, 2021), Ndubuisi continues with the tradition of questions which he established in his first collection, One Call, Many Answers (Communicator’s League, 2017). Perhaps, his Igbo subconscious is manifesting itself in one of its major ontological doctrines that “onye ajuju anaghi efu uzo,” loosely translated to mean that an inquisitor never misses the way. This could explain his choosing the pathway of inquisitions in lieu of assertions, given that some situations are so hard to swallow that one, in order not to go insane, poses questions, even if rhetorically, to avert the damaging reality that knowing brings. Hence, in sixty-seven poems, splurged over ten sections, Ndubuisi sets up an inquest into unraveling how Nigeria became a country, in the first place; into why Nigeria went on to unleash one of history’s biggest blood baths on Biafra; into why Nigerians allowed a backward man like Buhari to govern them for eight years; into Chibok, into such heartbreaking events as abandonment, etc.

In answers, Ndubuisi is an irritating gadfly, buzzing with redolent questions that unsettle those that are standing on “The way answers come.” For Ndubuisi, answers come “in millipede’s streams/ dragging many legs on the face of the earth/ that gives it dust enough to live” (10). In the poem “To a returning general,” the poet encourages us to offer “Fourteen gunshots for the old general who belongs/ to nobody and for everybody, who must answer/ the surname of herds” (12). Here, the poet believes, like many other Nigerians that the immediate past president’s assertion that he “belongs to nobody,” in his now infamous 2015 inaugural speech, is a covert allusion to his unwillingness to be accountable and time did prove it. Hence, “When you said…,” with its compelling imageries, reads like the angry outbursts of a disappointed citizen who caught the former general in his Daura farm, seizing him by the jugular began to reprimand him for his many unfulfilled promises that drove unsuspecting and change-hungry supporters into discarding objectivity, in the hasty run-up to his election:

When you said lies will steer the strife

of your predecessor, we, eager parliaments

parroted your creed, coveted your rhetoric…

we kept our doors open for the guardian star,

but here we have the scars of multiple stabs,

yours now outnumbered the vilest of them. (13)

The poet, speaking for every disillusioned, change-craving Nigerian, writes in the last two stanzas thus:

When you said our earth needed a new song,

we hailed and heralded you as the truth

of a twilight rumour, here, we rummage

our memories for traces of truth.

I waited through still-birthed answers after you,

slay man called me silkworms of doubt,

now we chew silences as peoples of hope. (14)

What, rather, disgusts the poet the more is that the maladministration is upheld by a section of the country as excellent. Buoyed by ethnic sentiments, the herd of mulish supporters eagerly pounce on any voice of reason and caution, especially if that voice is coming from the other divide of the country. The poet laments thus: “Kinsmen ready for war on the gust of the rumours/ of truths, tribal onslaught against logic seems/ the language of this union, tottering to a collapse…” (17). In the run up to this essay, I had a conversation with the poet over this particular poem. He confirmed that he was among those infested with the lies of the messianic packaging that was Buhari, he regretted that he contributed immensely, and wrote essays in support of the “monumental failure,” to use his own words. Tired of the inconsistent and disrespectful lies of the nation’s vaunted unity and immeasurable progress under a hopelessly nepotistic leadership that tugs at the sanity of citizens, the poet writes in “Unstuck” that he is free “from the debris of aged lies” (35). He literally detached himself from and, rather, elects to protest in the subsequent poems, as I will reveal.

In the titular poem, “Answers through the bramble,” the poet assumes the dissident voice of a revolutionary – you could almost hear the voice of Malcolm X if you read the words aloud. It carries the same intensity with which Malcolm delivered “By Any Means Necessary” in 1964:

The lungs will wake in the thorns

of scars. The sun will pierce

through the dark clouds. A song

gathers in this wind-froth pipe,

waiting for birth and rebirths… (46)

The poet pleads guilty to dissidence, making no attempts to disguise his repulsiveness: “I come in one voice with many lungs/ for answers. I come as quakes troubling/ the complacent class” (“Metalect, 47). Indeed, questions deserve answers, especially non-rhetorical ones, hence you could see the poet’s hostility towards silence. Hoping that “answers” could “claim… tongues of fires” (46), he makes a bold assertion that “The answer is a slave to a call…” (51). Consequently, in “Waiting answers” we learn that “… answers wait for moments when voices will be arrows,” answers:

come like rains, too rude

for the courtesy of praises.

They come again like redolent dikes

and leap through zebra zones

to make funeral chants of hyena’s

carnivals. (53)

Reading “Naija is a badly behaved poem” (55), one can then appreciate Ndubuisi’s hypothesis as to why the Biafran question still rages: “And you wonder there are cataracts of Biafra in the goiter of IPOB?” (58). For Ndubuisi, something begets something – the injustices and disequilibrium in Nigeria, for instance, begot Biafra; the callousness of the men in power, be it the governor, minister, president or the police officers that killed Tina in the poem in page 78, or the indulged terrorists that kidnapped the Chiboks Girls, or the herdsmen and their disguised ethnic cleansing, all begot the crux of this collection and the poet poses uncomfortable questions, that we may find liberating answers.

The collection is not just fires and brimstones. Indeed, the revolutionary can also muster sparks of love, as in Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu, Pablo Neruda, Malcolm X, etc., hence Ndubuisi approaches the themes of love in this collection like an experienced surgeon, laying out the intricacies of loving, living and contriving to summon laughter amid the countless infernos. Ndubuisi is unashamed in his profession of love to his mother, Kanebi; for his childhood crush, Ifunanya; for his friend, Barth Akpa, for the outstanding poet, Remi Raji, whose writings he admires and for his fiancé and muse, Antoinette, for whom he confesses: “I’ll be all-shine, and you, my star gift for a lifetime,” (95).

Beyond the theme of love, Ndubuisi handles the theme of grief and loss even more deftly, especially with the maturity with which he handled the possibility of his father’s abandonment of him and his mother after his birth. It was devoid of bitterness and recriminations, instead, we hear a voice refusing to accept the failure he was projected to become. Christopher Okigbo, Chinua Achebe, Pius Adesanmi, Harry Garuba, and victims of Boko Haram insurgency, all come alive in the befitting tributes that attest to the poet’s humanity.

In answers through the bramble, Ndubuisi continues to negotiate his poetic agenda from One Call, Many Answers. He ideates poetry as a response to memory, history, and the daily sociopolitical pressures. One notices, in the collection, that he pursues two dialects of poetry – the privatist tone – which would tax the interpretative ability of his readers – and the public or collective voice – which, of course, relates the quotidian in the voice that serves everyone. On the whole, Ndubuisi’s poetic vision is located in poetry as a philosopher’s kernel and the personal-collective imagination of a world accessible to trained minds and the public, particularly in the public themes that he pursues as imaginative access and answerability.

Average Rating