The Colours of Silence

Water

At first, you are like water: you absorb everything, break, stretch, coalesce and then flow again. People say you are too soft spoken. They do not know that when harsh winds come, water can be harsh too. You later absorb shades too thick and become bloody.

Before you are bloody, you whisper your best friend’s name each time you feel broken. With time, he grew tired of you. For him, a fourteen year old in his first year of senior high school, girls flowed faster in his mind than your issues, your mind’s colours transforming from butter to water and then blood. In the early days of your tender friendship, once, you said, “Did I ask for your help? Mind your business!” Buddy replied, “You are my business bro.”

Now Buddy tells you to be independent and stop sharing your feelings. There’s no such thing as a therapist here and you can’t trust any of the school counselors not because this is Nigeria but because of that large yam in your throat whenever you attempt to walk to the office. Being both the school chaplain and head of the counseling unit, the best of them, the one always flashing her coconut-white teeth would polish your secrets and turn them to case studies for devotions. You have watched this happen a few times.

You keep shut and all the deep things you’ve shared with Buddy become knots in your chest. You promise yourself to never again be so open. You don’t tell anyone the deep heart-wrenching stories. When they become too overwhelming, you weep and whisper, mostly on your pillow, in between heavy sobs, Buddy’s African name, Bodunde, though your English tongue Grandma continually reminds Mama to work on will never get it. You don’t bother. What bothers is that Buddy doesn’t know some guys are liquid and it isn’t shameful. Buddy is an ice cube. Nearly everybody likes ice and cool things. He has a lot of good things and friends too. He doesn’t freeze them, he cools. He isn’t liquid like you. Sometimes you envy him, you wish you weren’t the one with the disease, with stupid parents that only knew how to break everything and fight always, you wished that silly Physics teacher surprisingly close to your mum had not told the whole school you were a sickler even though that was the smallest of things. There were really worse things. Really worse.

Nonetheless, you hated the silent pity-showering and whispers whenever you were away from school. You hated that Physical Education teacher, a dirty thing, not a human, to you, who said he didn’t want a “medically limited” boy on the school football team. You hated how all eyes pierced yours suddenly. The man’s face is a field of sores, boils and pimples, so dense that you can’t differentiate them. You wonder how the new ones find space to grow. How dare he? How could he matter? How could a thing matter? How could a thing call you ‘limited’?

On broken nights when hope seems a fantasy, when you whisper Buddy’s name though he has turned his back, while budding girls float on his mind, you struggle to stay afloat. Soon, you stop absorbing all like water. You switch from colorlessness to blood. Later, a beautiful figure eight girl teaches Buddy how ice can still be broken. You wouldn’t know when this happens.

Yellow

Like red blood cells, if we view your fragments singly, we would see yellow. But together, they form a deep, stark, harrowing red hue.

Bloody boy, your mother sometimes calls you Yellow and you shudder when a stranger calls you by your first name in Yoruba, not English. Your name is not as heavy as your classmate’s, Onyeaghalanwanneya or one that makes people in your class chuckle like Umimmuna or Manifested. The name, though Yoruba, is special to you despite spending your first ten years in the U.K.

With time, as you noticed how bodies entrapped in wrinkled flesh but full of mysterious stories, unavoidable old people you had to prostrate for called Collins Calling instead and Samweh rather than Samuel, you called yourself Iyanuoluwa, not Miracle. Even though they meant the same thing, you felt you could not take the risk of hearing Miraku.

Before your color switched to water or blood, you believed June was just as yellow as your name. There isn’t summer in Nigeria – just rains and harmattan – but in your mind, once it is June, all is yellow and butterflies flap colored wings within you. To you, June is perfect, not just because you were born in June or because the school year approaches its end but because you often travel abroad in late June or early July. You hate Nigeria.

You did not know that yellow could fade. You didn’t know you were born in a hospital with yellow walls, with a fat silver spoon in your mouth and butter. Yellow life appeared normal to you. It isn’t.

Grey

The yellow faded. It happened in June. From then on you no longer whispered, “if we wear native attire to the altar, is it an alternative?” or “if we wave at a dwarf, isn’t that a microwave?” into your mother’s ear. You stopped such jokes, they weren’t funny and you couldn’t even try to be funny anymore. You left the school dance club and began to spend free time in your classroom, sleeping, drawing melancholic things or weeping. You sat close to the window, staring at nothing. You reached a breaking point where you had become too used to grief to feel anything. Numb, detached.

Your class teacher, that man whose mouth was constantly smelly, commented on these things in your report card. Neither of your parents read it. When last did they care about such? Your father simply removed the school bill and handed the envelope to you.

That June stole your yellow in many ways. You were rushed to the hospital too often. You couldn’t join the school team. You had to pretend you didn’t hear the cruel jokes when you resumed. You hated to be pitied.

And greatest of all, you recalled one night too vividly, too frequently. A starry Sunday night in which you pressed your right ear to your parents’ bedroom door. June 8 or so.

“I have no business with that unwanted boy.”

“Haba!” your mother exclaimed.

“Which one is haba now? Why are you pretending? Didn’t you want him aborted as well? It was that your doctor friend of yours that started giving you speech and you listened. I have said it to his face before. He is unwanted, useless. I will keep on spending money until I’m tired. And that is fast approaching. Eh, fifteen years after, of what use is he? You are here telling me you are noticing suicidal behaviors. What is my business? If he wants to die, let him die. It’s less stress for me.”

Your father hissed.

The pains all over your body felt worse and you badly wished death – painless, light. You watched the lights within you dim, rise and dim in an unsteady rhythm until everything shut out.

It was then you met Buddy, Bodunde. You thought maybe there was another chance of yellow. Ice cubes don’t give second chances, do they? After a while, as you were spilling it all, just to attain yellow, Bodunde told you to be independent, that it was so unmanly of you. Stop all this emotional rubbish, he had shouted. He turned his back and watched your colours switch from butter to water and then blood. Bodunde was an ice cube and to him, you really did not matter, everybody liked ice. Ice was popular and cool but a soft, liquid depressed boy like you wasn’t and never could.

White

Two years after, another thing happened in June.

In your final year of high school, after switching from yellow to different hues, you began to chase white. Everybody now preferred white to ice cubes. At least you could try and attain white, it wasn’t as hard as ice. This white wasn’t purity – that only stayed on the school motto. It was physical immaculateness. Six packs, standing shirt collars, designers’ shoes and schoolbags to change from Monday to Friday.

You were almost there when Buddy spoilt it. You were becoming popular and people said cool things about you. One Sunday afternoon, he caught you chasing a private kind of white. You were in the toilet stroking your thing with fair Ibinabo’s curvy body in mind. And when a white softness splattered on the toilet wall and Bodunde used the toilet right after, he knew all. You saw this mischievous glint in his eyes later on. Within a few days, he spread the story.

You switched to the color of silence.

Azure blue

You meet Buddy, Bodunde, in the sky. Both of you are waiting to use an airplane toilet. You have lived ten years with heavy guilt, black ants in your chest, thinking he died in the school toilet. You gasp, hug, weep and more things happen. Buddy becomes your best man at your wedding.

But before all these, fury consumes you. You fight Bodunde in class, lose two teeth and two weeks of school. You still don’t stop.

You fight him again in the hostel toilet after the suspension. You break porcelain, bottles, teeth and you still don’t stop at the sight of Buddy’s blood even though you fear blood normally. Ibinabo strokes your chest, screaming your name but the panging “Kill!” in your head is louder. And when Buddy becomes limp and the silence is so thick, you eventually realize your deed and weep, wondering why you committed your worst sin on a Sunday night.

Ten years after, on a Sunday night, you weep again. This time, you are in Bodunde’s arms, in front of a toilet above earth, above all things broken.

You become bluer than the sky.

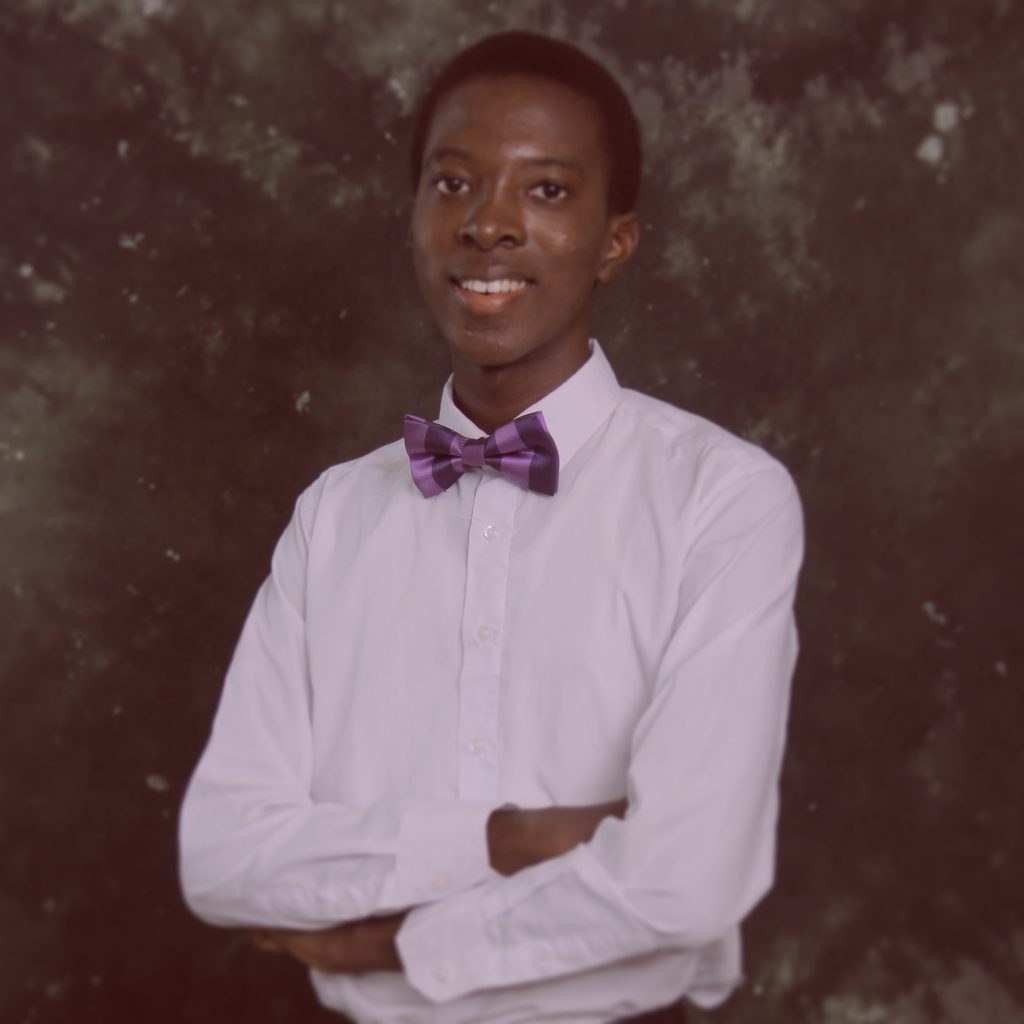

About the Author

Ifeoluwa Olatona, Nigerian, is a full-time reader, sometimes-editor and

award-winning 16 year old writer. He won the 2018 Channels T.V Prize for

Literature. He was named a Foyle Young Poet of the Year 2019 – the world’s

biggest award for poets aged 11-17, with over 11,000 entries in 2019 – by

the Poetry Society U.K. He wishes he could stop fussing over awful drafts

and reckons he can live a month eating nothing but plantains and drinking

nothing but milk.

[…] Ifeoluwa Olatona, Nigerian, is a full-time reader, sometimes-editor andaward-winning 16 year old writer. He won the 2018 Channels T.V Prize for literature. He was named a Foyle Young Poet of the Year 2019 – the world’s biggest award for poets aged 11-17, with over 11,000 entries in 2019 – by the Poetry Society U.K. read here https://www.ngigareview.com/2019/10/short-story-the-colour-of-silence-by-ife-olatona/ […]